Baffled, bewildered, at a loss for words to describe the kind of “contemporary art” that I appreciate the most, I finally came across six words that struck a chord in me. Steve Martin wrote in his novel, Object of Beauty:

“Her addiction to energy kept her pushing on, snaking between Tenth and Eleventh Avenues, down 20th Street and beyond, until the mood gave way to mundane galleries presenting new art in the old way.”

I can relate to that kind of addiction of going from gallery to gallery in hopes of seeing a work of art that might wow me. It’s rare to find one in the Chelsea art gallery district of New York, but I have found extraordinary works in “galleries presenting new art in the old way.”

Artists (left to right) Elizabeth Beard, Dale Zinkowski, and founder of Grand Central Atelier, Jacob Collins, and Patrick Byrnes, look at artwork at the opening of the “Wrap Me Up: Winter Small Works Show” at Eleventh Street Arts gallery in Long Island City, New York, on Nov. 17, 2016. (Samira Bouaou/Epoch Times)

Artists (left to right) Elizabeth Beard, Dale Zinkowski, and founder of Grand Central Atelier, Jacob Collins, and Patrick Byrnes, look at artwork at the opening of the “Wrap Me Up: Winter Small Works Show” at Eleventh Street Arts gallery in Long Island City, New York, on Nov. 17, 2016. (Samira Bouaou/Epoch Times)

That phrase, “new art in the old way” reminds me of art that should not be called contemporary art. It reminds me of paintings that are best presented on neutral, darker, low-chromatic colored walls—not in “white box” galleries. This kind of art has to be seen in person. It does not photograph well, and it certainly does not need convoluted, pretentious, theoretical language to justify it as art.

At the end of my previous post, I riffed on Steve Martin’s phrase. I wrote, “artists who make new art in the traditional way.”

Why did I supplant “old” with “traditional” you might ask?

Honing the techniques, skills, and tools for creating works of art at the level of the old masters is an infinite process. I replaced “old” with “traditional” because the old way is actually not old, but timeless.

I associate the word “tradition” with convention, a particular kind of reserve or measured restraint, and responsibility. Apart from the benefits that derive from those modes—a sense of security, a certain degree of predictability, and solidity, to name a few—there’s also a freeing aspect to tradition that I want to highlight.

You might find it unusual to pair “tradition” with “freeing.” I’ll try to explain.

When you follow a tradition, you slowly relax into a sense of something that is greater than yourself. That, in and of itself, is freeing.

Let’s take the oil painting tradition of Western civilization as an example—a tradition that sadly has been disparaged of late in the past century (but I won’t go on about that here). In the oil painting tradition, you would be uniting with a community that extends beyond the present time—with master artists who died in the past and with artist who are yet to be born in the future. This is freeing because you are not under the pressure of having to reinvent the wheel from scratch, of having to create something that is entirely “new,” as expected of “contemporary” artists. Instead, you stand on the shoulders of people who became masters as they grew through surpassing their unique challenges. Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Rembrandt, Velasquez, Ingres, and many others, solved problems that you can learn from and perhaps develop further.

As you connect with this beyond-biology lineage, you become more humbled; and as you develop your own vision, within the form of that tradition, you expand. Your contribution to the tradition perhaps renders the culture a little bit more enriched and exquisite.

Artist, Edward Minoff works on his seascape painting, tittled “Foundation, Triptych” in his studio in Brooklyn, NY, on August 22, 2018. (Photo: Milene Fernandez)

Artist, Edward Minoff works on his seascape painting, tittled “Foundation, Triptych” in his studio in Brooklyn, NY, on August 22, 2018. (Photo: Milene Fernandez)

Even more significant, in your sincere search for beauty—which is a strong aspect of that tradition—there’s a possibility of connecting with a sense of the divine.

It doesn’t matter whether you are a believer of a particular faith or not. It’s innate in us as humans to want to feel connected to something greater than our mere selves. I don’t believe anyone willingly wants to feel alienated or trapped within their own skin. If anything the year 2020 showed us is that we don’t do well in isolation; we are deeply interconnected.

Far away from city lights, what do you feel upon seeing a star-filled sky? Perhaps you have felt that humbling sense of wonderment at the infinite vastness of the universe, or peaceful while listening to the sound and rhythm of ocean waves, or hopeful when seeing a baby sparrow taking its first flight or exhilarated while listening to music by Johann Sebastian Bach. (By the way, my favorite is the album: JS Bach Keyboard Concertos interpreted and played by the pianist David Fray). These are a few examples of when I have felt a sense of the divine.

The late philosopher and writer, Sir Roger Scruton (1944–2020) once said, “The search for beauty actually is an attempt to rediscover that condition in which we were in once, before separating ourselves from the natural order.”

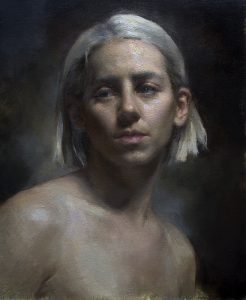

Oil painting, “Ruby” by Rachel Li (b. 1995).

Oil painting, “Ruby” by Rachel Li (b. 1995).We human lot are flawed beings—some more than others, but flawed nevertheless—otherwise we would all be perfectly content at all times. So, we have collectively created tradition to make up for our condition, to give us a sense of home, to remind us that we could be better, and that it’s worth striving to be better, to strive towards an ideal.

The ancient Greek philosopher, Plato (429?–347 B.C.E.) wrote: “At the sight of beauty the soul grows wings.” Maybe in appreciating and furthering a tradition our wings begin to grow, we feel lighter, freer, and a little bit more content.

It’s comforting to recognize our inability as mere individuals to create the sense of home that tradition gives us. It’s created within a community that transcends time. New art in the traditional way gives solace.

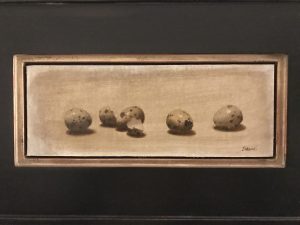

“Quail Eggs II” by Dale Zinkowski. Oil on linen, mounted on panel, 2020.

“Quail Eggs II” by Dale Zinkowski. Oil on linen, mounted on panel, 2020.